Some called him “Santo Cecilio”; others, “the Mozart of mariachi.” To members of Mariachi Vargas, he was affectionately known as “El Chachalaco.” Regardless of what you called him, Pepe Martínez was a towering giant of mariachi music—a musical figure that none of us who had the privilege of knowing him will ever forget. Four years after his passing, mariachimusic.com and the Mariachi Vargas Extravaganza pay tribute to Pepe Martínez on what would have been his 79th birthday.

José Martínez Barajas was born on June 27, 1941, in the southern Jalisco village of Tecalitlán, where he demonstrated a vocation for music at an early age. Although the group led by Silvestre Vargas, previously considered the best mariachi in town, had moved its home base to Mexico City six years prior, mariachi music remained alive and well throughout the region, and that was what young Pepe grew up listening to.

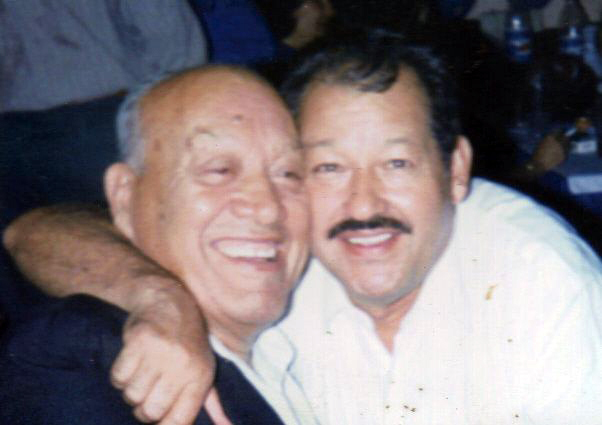

(courtesy of Rosario Martínez)

Pepe’s father, Blas Martínez Panduro, was a harpist who built and repaired musical instruments, but his activities as a musician and a luthier were barely enough to make a modest living. Don Blas observed his son’s compulsion to learn to play every instrument that came through his shop. At a young age, Pepe discovered that he had perfect pitch. When his older brother, Rafael, gave him a solfege method, a lifelong fascination with written music was born in him. In his soon-to-be-published autobiography, Pepe himself recalls:

Many times I found myself amazed at the effortlessness with which musical notes entered my head. I’m serious about this. It was as if I already knew those symbols, as if that information had been previously stored in my head and all I had to do was remember it.

Pepe’s father, on the other hand, had no use for ‘fly specks on a page,” as he called musical notation, something he considered frivolous and inapplicable to mariachi music. In Don Blas’s opinion, Pepe’s solfege studies were a complete waste of time. “Just learn the sones they ask for in the chambas,” was his advice to his son. When the Martínez family moved to Guadalajara in 1950, Pepe discovered that most mariachi musicians there were of the same opinion as his father.

(courtesy of Rosario Martínez)

In Guadalajara, Don Blas found work with Mariachi Los Charros de Jalisco, but money continued to be scarce for the Martínez family. To help put food on the table, Pepe shined shoes, sold chewing gum, and did anything else he could to earn a few pesos. In 1953, he organized his own four-piece mariachi of fellow elementary school students. He named the group Mariachi San Andrés, after the neighborhood they lived in. The group’s personnel was Pepe Martínez, guitarrón; José Luis Rodríguez, vihuela; Agustín Alaniz “el Picudo”, 1st violin; and Columbo Méndez, 2nd violin. The quartet played on city busses every weekend, and Don Blas made an extra-small guitarrón for his son especially for that purpose. “But don’t assume we played on busses because we didn’t know anything,” asserts Columbo Méndez, Pepe’s lifelong friend and musical companion. “We all sang, and we knew all the popular songs of the day. The best singer of the group was Pepe.”

One day, purely on a whim and without notice, the foursome decided to take an unplanned excursion to Tijuana. Between trains, busses, and hitchhiking on trucks, the boys made it to their destination by playing and singing for drivers and ticket inspectors along the way, who in turn let them ride for free. Not until arriving in Tijuana several days later did they bother to let their parents know where they were. Although the quartet earned good money in Tijuana, in his autobiography Pepe reveals another motivation for that unscheduled trip to Mexico’s northern border:

I went there hoping to find trained musicians who could guide me on my quest. That didn’t happen. We came back disillusioned because the mariachis there were the same as the mariachis here: nobody wanted to rehearse or practice, and nobody proposed anything new. Furthermore, the border repertoire was much more limited than it was in Guadalajara. After a month, we returned.

At around age 15, Pepe joined the official mariachi of the Mexican Army’s 4th Infantry Division, where his father was a member. By this time, Pepe had switched to violin. General Bonifacio Salinas Leal was so impressed with the boy’s talent that he gave him a scholarship to study at the University of Guadalajara School of Music, where Pepe began his first formal training. There his violin teacher was Maestro Ignacio Camarena of the Orquesta Sinfónica de Guadalajara, and his solfege teacher was Maestro Luis Sánchez Rivera of the Banda del Estado de Jalisco. Columbo Méndez recalls:

Pepe and I began studying music at the same time, but he learned so fast that he left me in the dust. Before I could get through the second volume of Solfeo de los Solfeos, he had already finished the third one! It seemed that Pepe was always quicker and learned faster than anyone else.

In 1959, Pepe formed his second youth group, Mariachi Los Tigres de Jalisco. Columbo was part of that ensemble, too. He remembers:

Before making our debut, we rehearsed every single day of the week. After four months, we had 70 songs under our belt. When we’d go out to the plaza, other mariachis would ridicule our tiger-skin jackets, so we eventually discarded those and renamed the group Mariachi América.

After about a year, Mariachi América disbanded. Around 1960, Pepe joined Mariachi Metepec, the official ensemble of Compañía Industrial de Atlixco, the second largest textile mill in Mexico, which had its own mariachi. He didn’t remain there for long, however. Roberto Pinzón “El Chocolate” (nephew of Juan Pinzón), a member of Mariachi Perla de Occidente at the time, tells the story of how he and fellow bandmember Lázaro Chávez (of Mariachi Los Monarcas fame) traveled to nearby Puebla to invite Pepe to their group:

When we showed up in Metepec, the mariachi was rehearsing. After greeting Pepe, we got down to business: “You’d said you were interested in playing with us, and we’re here to formally invite you to our group.” “Sure,” Pepe replied. “I’m not under any contract here.” “Great,” we told him. “How much time do you need to tie up loose ends? A week? Two weeks?” “Give me five minutes!” replied Pepe. And he threw the few clothes he had into a tiny, cheap cardboard suitcase and returned with us to Mexico City.

Mariachi Perla de Occidente was one of the most respected mariachis in Mexico at that time. It was considered a training ground for Mariachi Vargas, since Jesús Rodríguez de Híjar, Rigoberto Alfaro, Juan Pinzón, and Federico Torres had all been members of that group before joining Vargas. Besides making dozens of records on their own, the group had accompanied and recorded with Pedro Infante, Javier Solís, Antonio Aguilar, Charro Avitia, Cuco Sánchez, La Torcacita, Dora María, Hermanos Záizar, Hermanas Padilla, and many other famous artists. Mariachi Perla also accompanied Amalia Hernández’s Ballet Folklórico de México. Pedro Rey (Pedro Hernández) was the group’s trumpet player at that time. “As members of Mariachi Perla, Pepe and I accompanied Miguel Aceves Mejía on a tour of Perú around 1961,” recalls Pedro. Columbo Méndez was also a member of Perla de Occidente at that time. He recalls fondly how he and Pepe would run after cars on Avenida Niño Perdido (the thoroughfare bordering Plaza Garibaldi) hustling potential customers for the group.

Roberto Pinzón was one of the musicians Silvestre Vargas would frequently call when he needed an additional violin for a Mariachi Vargas recording session. One day Silvestre asked Roberto if he knew of another violinist who could read well, and Roberto took Pepe with him. It was in that session that Pepe Martínez met Silvestre Vargas for the first time. “Where are you from?” Silvestre asked him. When he said he was from Tecalitlán, Vargas asked him who his father was. “Blas Martínez,” he replied. “Your father used to play in my group!” exclaimed Silvestre in astonishment.

Roberto continues the story:

Silvestre Vargas kept inviting Pepe and I to recording sessions, until one day I overheard Vargas ask him, “Hey, Pepe, how would you like to work with me?” “I am working with you,” was Pepe’s reply. “No, I mean de planta,” Vargas clarified. I was standing right next to them, and Pepe turned to me and said, “Did you hear that, Choco? Did you hear what he just said to me?” I immediately piped up: “Hey, Vargas, don’t you like the way I play? Why don’t you invite the two of us?” “No, Choco,” Vargas explained. “You’re my right-hand man whenever I need an extra violin, but I want Pepe to be a full-time member of my group.”

For whatever reason, Pepe never accepted that invitation, and it was something he never spoke about in later years. Had he accepted, his career would have undoubtedly been different. Although Pepe already loved to direct rehearsals and mount songs and instrumental pieces with groups, he was just beginning to write his own musical arrangements at that time.

After a little over a year in Mexico City, Pepe and Columbo returned to Guadalajara where they revived Mariachi América, the group that had broken up before they left for Mexico City. After a few months, however, José Santos Aguilar convinced Pepe and fellow América violinist Miguel Camacho “El Platanero” to join his group, Mariachi Los Rancheros, and Columbo took over the leadership of Mariachi América. But Pepe didn’t remain long with Los Rancheros, traveling soon thereafter to San Fernando, California, about a half-hour north of Los Angeles. Trumpeter Antonio Hernández of the Hernández dynasty picks up the story from here:

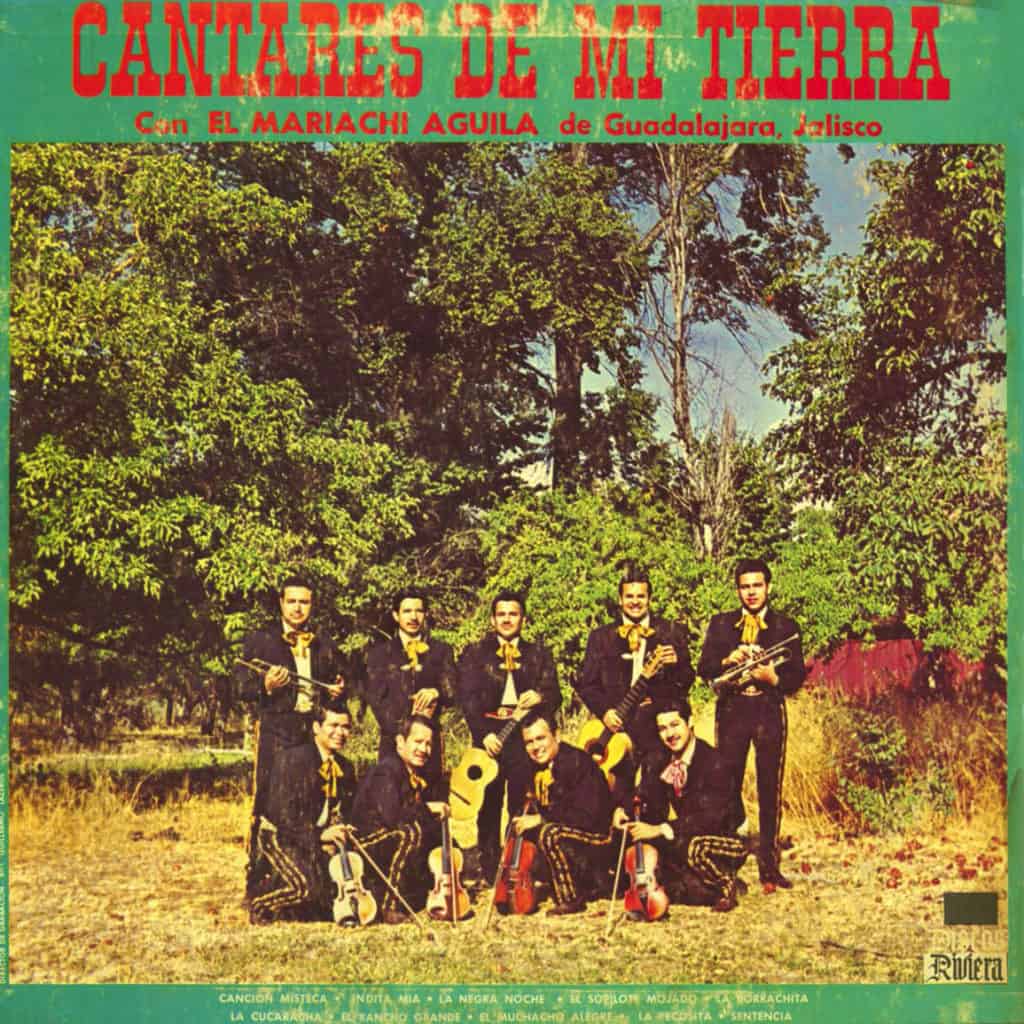

It was around 1962. At the time, I was a member of Mariachi Águila, led by Rafael Aguilar. Members during that period included my father Esteban, my brothers Pedro and Chencho, Roberto Gutiérrez—and the great Miguel Martínez. Word came to us that there was a very talented young violinist in nearby San Fernando playing with a really perrada mariachi. Rafael Aguilar went there to see him, and Pepe accepted his invitation to join Mariachi Águila.

After Los Camperos de Nati Cano, Mariachi Águila was the most prestigious U.S. mariachi of that period, and they were Los Camperos’ most formidable competition. Águila was the only mariachi that encroached on Nati Cano’s turf, playing stage shows at casinos in Reno, Las Vegas, and Sparks, Nevada, like Los Camperos did at the time.

Front row: Roberto Gutiérrez “El Chaparrito,” Rafael Aguilar, Esteban Hernández, Pepe Martínez.

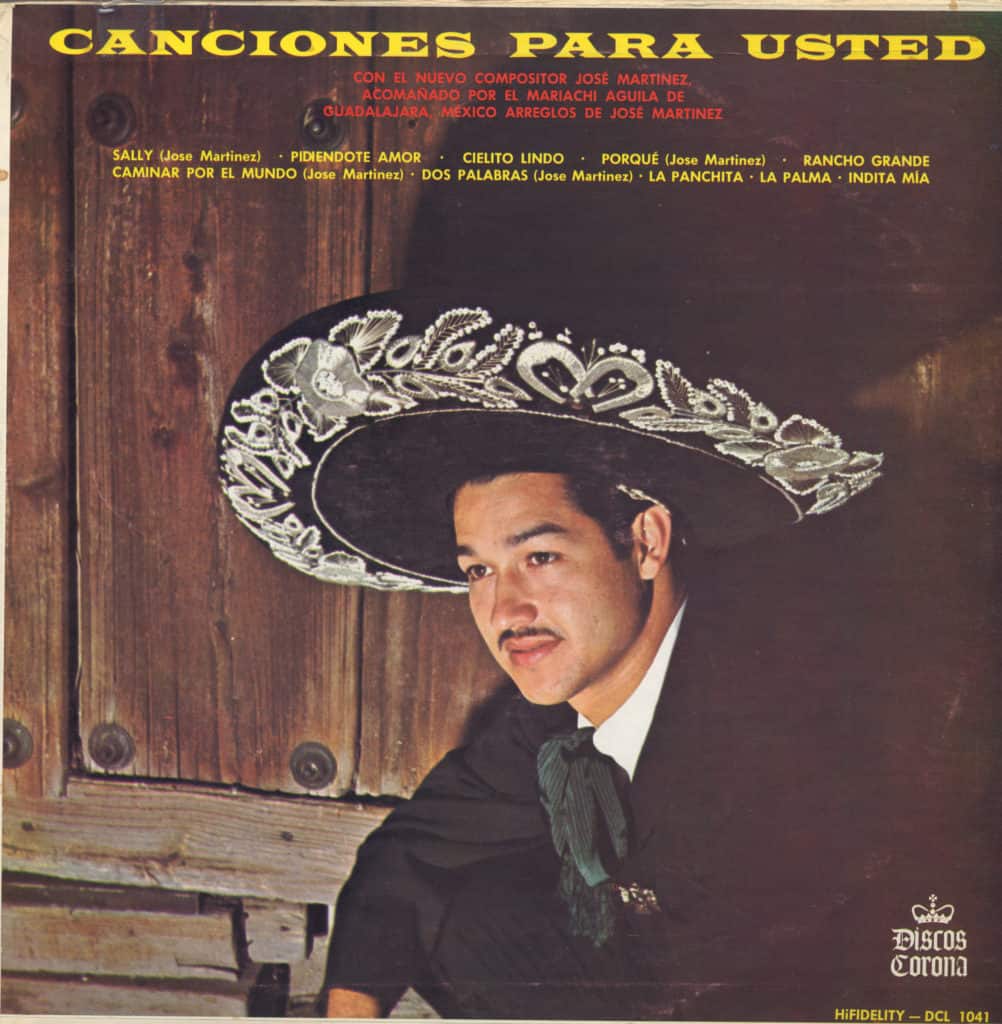

It was in Mariachi Águila that Pepe began to develop as an arranger. The group made at least six LPs for the Discos Corona label, many of which include his arrangements, and he made many more for records by local singers. In 1964, toward the end of his tenure with Mariachi Águila, Pepe made his own solo LP, one that is very much a collector’s item today.

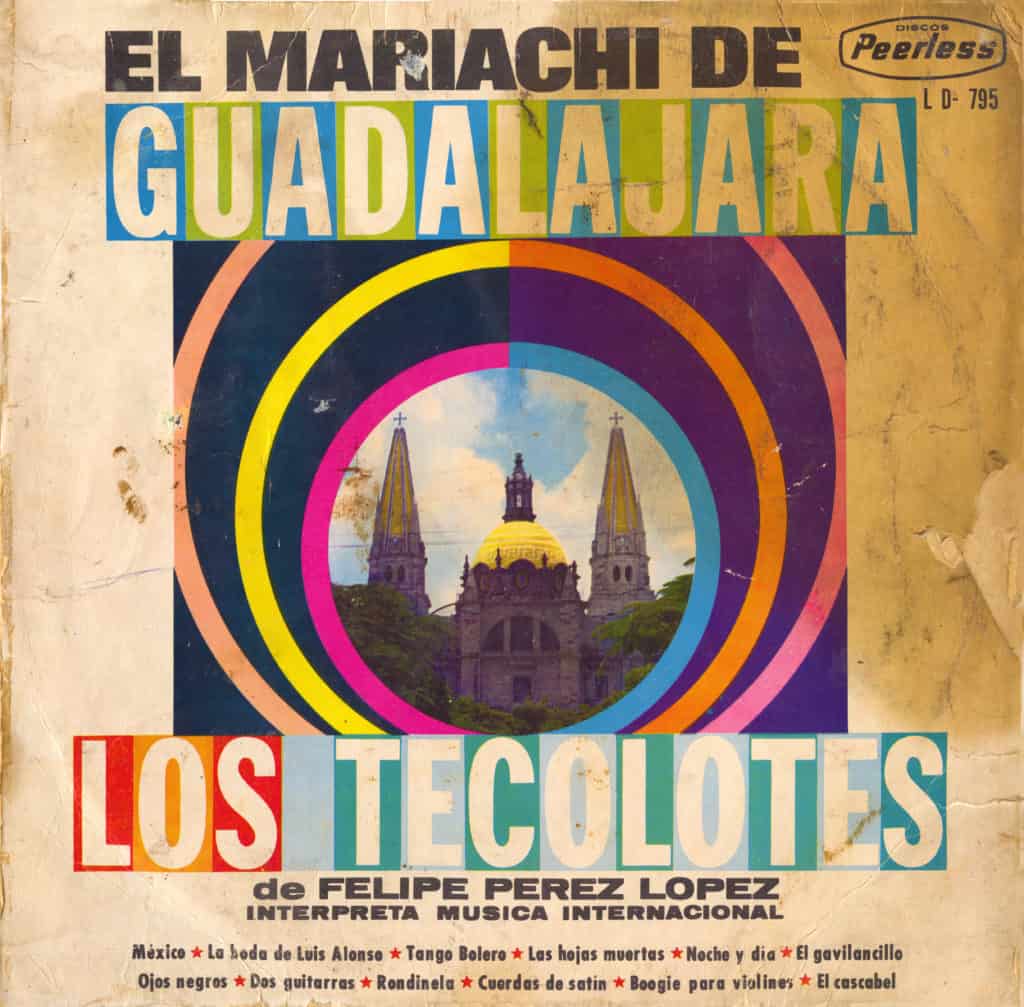

After a couple of years with Mariachi Águila, Pepe returned to Guadalajara where he joined the latest incarnation of Mariachi Los Tecolotes, now led by ex-Mariachi Vargas guitarist Felipe Pérez “La Panzona,” who would later become his father-in-law. In an improvised studio in Guadalajara, Los Tecolotes recorded an LP that was released in 1964 on the Peerless label. The album features several arrangements by Pepe, including the very first mariachi recording of “El Cascabel,” a son jarocho that Pepe had personally learned from Antonio Maciel.

Mariachi Los Tecolotes soon secured a contract to perform at a Los Angeles, California restaurant, and in 1965 Pepe found himself back in that city. But as fortune would have it, during the course of that engagement Los Tecolotes split up, each of its members going their separate way.

Back in Guadalajara, Pepe decided to once again try his hand at forming his own mariachi. He put together the best musicians he could find, many of whom he’d played with previously. The outstanding violin section was made up of Juan González, Miguel Camacho, Juan Elías, Julio Rodríguez, and Álvaro Reynoso. The original rhythm section was comprised of Gregorio Ramírez “El Güiloto” on guitarrón, Ramón López on vihuela, and José Hernández “El Ochenta Risas” on guitar. Juan Gudiño and Fernando Martínez were the trumpet players, and Pepe was violinist, arranger, and musical director. Since Juan González was the group’s business manager, it became known as Mariachi Nuevo Tecalitlán de Pepe y Juan.

Julio Rodríguez, Fernando Martínez, Pepe Martínez, and Juan Gudiño.

(courtesy of Juan Gudiño)

1965 is the official founding year of Mariachi Nuevo Tecalitlán. According to Juan Gudiño, the group originally didn’t have a planta, but rather would stand around nightly at the San Juan de Dios mariachi plaza, where customers would mainly hire them for serenatas, the group’s specialty. At times they would play around the tables inside El Ranchito, a restaurant-bar located on the plaza.

In 1968, Nuevo Tecalitlán became the house band for Cazadores Campestre, a spacious open-air restaurant in Guadalajara’s Tlaquepaque municipality that had previously featured only sedate salterio (psaltery) music. Nuevo Tecalitlán soon became synonymous with Cazadores and the restaurant became extremely popular, with Pepe and Juan’s mariachi being the prime attraction. (Juan González eventually left, and by the 1970s his name was no longer used as part of the oficial group designation.) Now widely considered one of the best mariachis in the world, Nuevo Tecalitlán’s reputation spread internationally.

Mariachi Nuevo Tecalitlán made its first long-playing record for the Musart label in 1966. Two LPs for Discos CBS in 1969 and 10 more for the Guadalajara-based AZA label that same year followed, but Monterrey-based Sono-Mex was truly the label that put Nuevo Tecalitlán on the map. As Pepe told the story, one day around 1970 José Luis Torres, owner of Discos Sono-Mex, came to see him. Pepe assumed the entrepreneur wanted Nuevo Tecalitlán to make an album or two for his label. But as it turned out, Torres wanted a series of 20 LPs, each one of a different musical genre or theme! Pepe signed the contract and started writing. When it came time for the group to travel to Monterrey, Nuevo León to record, he took an entire suitcase full of scores and parts with him.

Few arrangers would have accepted such an excessive assignment, but Pepe— who had always been an extraordinarily fast writer—took on the task. “I try to never spend more than one hour on any given arrangement,” he once told me. His speed and prowess at composing and arranging caused Mark Fogelquist to dub him “the Mozart of mariachi.” As Jesús Rodríguez de Híjar used to say: “Pepe is a veritable music writing machine.”

The Monterrey recording sessions were quick and dirty. Everything was live and direct with no overdubs. Second takes were rarely allowed, regardless of how many mistakes were made. The group recorded as many as two entire ten-song LPs in one day.

These Nuevo Tecalitlán albums were widely pressed and distributed in Mexico, the United States, and many other countries. They could be found everywhere—from record store bargain racks to supermarket bins to flea markets—where they cost less than half of what a full-price, name-brand LP (like those of Mariachi Vargas) sold for. After the initial 20 albums sold like wildfire, Pepe signed a new contract to make another 20. The over 50 albums released on AZA, Sono-Mex, Torres and other budget labels increased the group’s fame and made Mariachi Nuevo Tecalitlán, in terms of sheer number of records sold, probably the most prolific mariachi of the LP era.

—Jonathan Clark

Thanks for this excellent description of Pepe Martínez’ musical life! I truly enjoyed his presence with Mariachi Vargas at the San Antonio Mariachi Extravaganza year after year. No director of Mariachi Vargas since him has come close to his entertaining leadership during the performance.

Looking forward to Part 2 of this article.

Me gusto está reseña….. Mi pregunta sería….. Como c como ifton Juan Gudiño y Fernando Martínez… Como fue su brillo y estilo parecido en tocar la trompeta fue tan similar…. Y en q mariachi anduvieron antes….. Soy admirador del Nuevo Tecalitlán desde su disco Clásico Sonido Espectacular de Sonomex.

There at least four albums with Pepe Martinez and the Mariachi Vargas with my name on it as recording engineer in Mexico City in the mid 1970’s

Thank you, Jon Clark! Your tireless work on the history of mariachi does not go unnoticed. I’m looking forward to part two. As always, any info or documentation that I can be of help with is my pleasure to share with you. Keep up the great work!

Tu amigo de siempre,

John A. Vela

El Vargas siempre ha sido lo máximo, especialmente cuando el señor Pepe fue su director musical. Talento como ése se ve muy poco.

Amigo, gracias por describir a detalle parte de la vida de mi padre. Siempre te estaremos agradecidos por el cariño, que sabes es recíproco.

Un abrazo cariñoso y ¡felicidades por tan hermoso artículo!

Thank you for sharing Pepe Martinez’ musical biography. I didn’t know that he had been with so many musicians before Mariachi Vargas. I knew he was very talented but this article shows that he was a musical genius. Gone too soon.

May he rest in peace.

Thank you very much for sharing such a wonderful biography of our Pepe Martínez. We’ll always remember his beautiful smile full of joy!

Glad you liked the article, Beatriz. I’ve always enjoyed your gorgeous voice!

Jonathan

Great article, Jonathan. I wonder if Pepe Martínez was responsible for arranging some classical pieces? I have an audio tape of classical Mozart, Bach and other classical pieces played by mariachis. It’s an audio cassette with very little information about who the musicians are. Would you know anything about this?

Well, thank you again, Jonathan. I look forward to the 2nd part. Good work!

Glad you enjoyed the article, Carmen. Pepe arranged many classical works, both for Mariachi Nuevo Tecalitlán and Mariachi Vargas, but I’m not sure if those are the recordings on your cassette. I’ll talk some more about that in part two.

Saludos.

Excelente reportaje, mi estimado Jon! Detalles muy interesantes de este personaje tan querido y tan admirado como lo fue Don Pepe Martínez. Gracias por contribuir a la diseminación de la historia del mariachi. Espero con ansias tus futuros reportajes.

Hola soy la nieta de Juan Gudino. I’m very honored in this who till this day listen to my grandfather music he’s still alive well and still playing something he will never leave alone and still sounds great!!! I showed him this page and he is very honored and proud!!! He says Thank you to everyone that still listens to his music.