Marcelino Ortega, director of Mariachi Perla de Occidente for over half a century, died April 24 after a long bout with kidney failure. Perla de Occidente is best known for accompanying Pedro Infante and Javier Solís, and as a training ground for groups like Mariachi Vargas de Tecalitlán and Mariachi México de Pepe Villa.

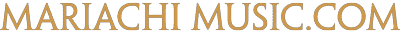

Marcelino Ortega Melecio was born in 1923 in Zacoalco de Torres, Jalisco — a town that, in his famous 1935 article, linguist José Ignacio Dávila Garibi considered one of the principal cradles of mariachi music. Ortega Melecio’s father, Marcelino Ortega Encarnación, born in that same town in 1889, was a valve trombone player who directed the local banda. In 1922 he married Serafina Melecio Patiño, and in 1923, Marcelino Jr., the first of their eight children, was born. Finding few opportunities for advancement in Zacoalco, in 1926, the family moved to Guadalajara, where Marcelino Sr. formed a small orchestra. In 1929, during one of the orchestra’s performances in Mexico City, he met mariachi pioneer Cirilo Marmolejo, who invited him to join his mariachi. Shortly afterward, the Ortega family moved to Mexico City, where Marcelino Sr. played with Cirilo Marmolejo’s Mariachi Coculense until 1933, when he left to form his own group, Mariachi Los Diablos Rojos. His son, Marcelino Jr., played guitarrón in that ensemble, which soon gained a reputation as one of the best mariachis in Plaza Garibaldi.

Marcelino Ortega Sr. playing trombone with Mariachi Coculense

de Cirilo Marmolejo in the early 1930s.

In 1941, Marcelino Sr. died unexpectedly. When it came time to vote for a new leader of Los Diablos Rojos, the musicians unanimously chose Marcelino Jr., even though he was the youngest member of the group. Their rationale, Marcelino explained to me, was that since father and son had the same name, there would be no need to print new cards or publicity photos, and the group could retain the name “Mariachi Los Diablos Rojos de Marcelino Ortega.”

Marcelino Jr. had distinct musical ideas from those of his father, and he promoted his group more energetically. Although Mariachi Tapatío de José Marmolejo was all the rage at that time, young Marcelino much preferred the sound of a lesser-known group from Tecalitlán led by Silvestre Vargas, which seldom used a trumpet player. Under the direction of the younger Ortega, the stylistic model Los Diablos Rojos followed was that of Vargas, and Marcelino Jr. even reorganized the ensemble so as to have the identical instrumentation as Mariachi Vargas of that era: five violins, vihuela, guitarra de golpe, guitarra sexta, guitarrón, and harp.

His father had been dead less than a year when young Marcelino procured an audition for Los Diablos Rojos at XEW, Mexico’s most important radio station. The station’s artistic director, Amado C. Guzmán, liked the group, but he didn’t like their name. Member Boni Collazo came up with “Mariachi Perla de Occidente,” and the name stuck.

The exposure from playing on XEW initiated an ascent in popularity for Mariachi Perla de Occidente. Among the many singers they accompanied on radio in those early days were Lucha Reyes, Jorge Negrete, Pedro Infante, and Matilde Sánchez “La Torcacita.” Extensive tours to Central- and South America, the Antilles, and fhe United States followed. They also began recording extensively, performing on hundreds of 78 rpm discs of the era. The group has appeared in dozens of films.

In the mid-1950s, Mariachi Vargas had a falling out with Pedro Infante’s manager, Antonio Matouk, who convinced Pedro to look for another mariachi. This was a major break for Perla de Occidente, as they became Pedro’s exclusive group in the latter part of his career — touring, making two films and recording ten songs with the legendary artist before his tragic plane crash in 1957. The crisis of Pedro’s death was exacerbated when the group’s two best musicians, Jesús Rodríguez de Híjar and Rigoberto Alfaro, left to join Mariachi Vargas. Mariachi Perla de Occidente never regained its former glory.

Marcelino Ortega and Rigoberto Alfaro, guitars.

Juan Pinzón is on far right.

After an extended slump, in 1961 Perla de Occidente became the official mariachi for Amalia Hernández’s famous Ballet Folklórico de México. This gave the group a steady salary and the opportunity to tour the world, which attracted numerous outstanding musicians, some of whom went on to join famous groups, others of whom started their own successful ensembles. No other mariachi in history has functioned as a seedbed for top-echelon musicians and groups to the degree that Perla de Occidente has. The following is a list of only some of the prestigious players who have passed through its ranks: Rigoberto Alfaro, Antonio Ceballos, Bonifacio Collazo, José Contreras, Miguel Díaz, Arcadio Elías, Leonardo Espinoza, Juan Güitrón, Pepe Martínez, Pedro Morales, Gonzalo Meza, Miguel Paredes, Cutberto Pérez, Juan Pinzón, Pedro Ramírez, Jesús Rodríguez de Híjar, Cipriano Silva, Federico Torres, Salvador Torres, and Manuel Valle.

In 1994, after 33 years with the Ballet Folklórico de México, Marcelino had an altercation with the grandson of Amalia Hernández that ended in a bitter lawsuit. Although the rumor mill in Garibaldi had it that he’d received many millions of pesos in a retirement settlement, Marcelino assured me that after 33 years with the ballet, “No me dieron ni siquiera las gracias.”

After the ballet era ended, Mariachi Perla de Occidente disbanded permanently, and Marcelino took to playing in Plaza Garibaldi, where he had started as a child back in the 1930s. Now in his seventies, and after half a century of leading his own group, he didn’t feel comfortable there. “When I have a chamba, everybody wants to go with me,” he said. “But when I’m looking for work, nobody wants me because I’m too old,” Shortly after that, his wife, Rosario Díaz Gaspar, had a stroke, and Marcelino devoted himself to staying home and taking care of her. “I sold all my trajes de charro, just so I wouldn’t be tempted to go back to Garibaldi,” he confided to me in a disenchanted tone. After the mid-nineties, Marcelino almost never visited Plaza Garibaldi, even though he only lived a few blocks away.

Not only was don Marcelino a good friend of mine, he was my ex-jefe, as I had played guitarrón with his group on one of the ballet’s tours of France in 1988. On my visits to Garibaldi, I would always ask for Marcelino. Most mariachis assured me he had died, and a few told me he had moved to Guadalajara, but mariachi friends there assured me none of them had seen him in that city.

After nearly a decade of inquiring about his whereabouts, I happened to ask Miguel Paredes of Mariachi México de Pepe Villa if he knew anything about Marcelino, not realizing they were compadres. “I’m certain that my compadre lives in the same apartment he’s always lived in,” Paredes assured me. I remembered where Marcelino used to live in the Colonia Guerrero, found the entrance to his tenement, and asked someone there where he lived. They pointed to his apartment, and when I knocked on the door, Marcelino answered.

We hugged each other, and a warm reunion followed. I found out that in the decade I hadn’t seen him, his wife had died, and that he was now on kidney dialysis. I knew Marcelino’s days were numbered, and I made a point to call him frequently and visit him every time I was in Mexico. A couple of weeks before he died, his nephew had informed me that his grandfather was in the hospital. I called back on the very day he returned home and talked to him briefly, but Marcelino sounded tired and I cut the conversation short. A week later I received a text message from his grandson saying don Marce had just succumbed to a heart attack.

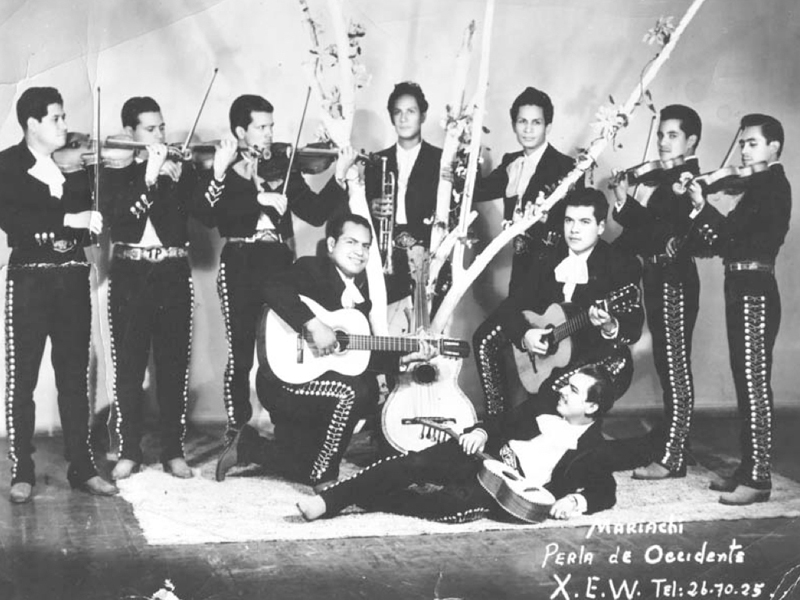

Antonio Covarrubias, Jonathan Clark, Marcelino Ortega, Juan Pinzón, and Miguel Martínez. Homage to Marcelino Ortega and Juan Pinzón on behalf of the Unión Mexicana de Mariachis. Plaza Garibaldi; Nov. 22, 2011.

In a case similar to that of don Miguel Martínez last December, don Marcelino Ortega died on a Friday afternoon, so it was difficult to get a full mariachi group to come to the funeral home for the wake, although many individual musicians came to pay their respects. He was scheduled to be cremated at noon the following day.

Concerned that her father was going to be put to rest without a proper mariachi sendoff, early the next morning his daughter Lourdes ran to Garibaldi to see if she could hire a group to play for her father before he was taken to his final destination. “The first person I ran into was an elderly mariachi musician,” she told me. “I explained the situation to him, and he proposed that I get the driver of the funeral vehicle to bring the casket to Garibaldi on the way the crematory. He assured me that every musician in the plaza either knew or knew of my father, and would be glad to play for him.” She did as the man suggested, and all came out to the avenue to bid her father farewell, as can be seen in the video below. More mariachis would have been present had it not been so early in the day.

Garibaldi musicians pay their last respects to Marcelino Ortega.

(Courtesy Centro del Mariachi)

Que en paz descanse, don Marcelino. Nunca le olvidaremos.

Su amigo de siempre,

Jonathan Clark