Renowned for his abilities as a trumpeter and his lighthearted, jovial character, Jesús Oliva “El Bolis” succumbed to heart failure on April 30, 2020 in Culiacán, Sinaloa. Oliva held the distinction of having been part of Mariachi Vargas de Tecalitlán’s earliest attempt at establishing a trumpet duet, in 1960.

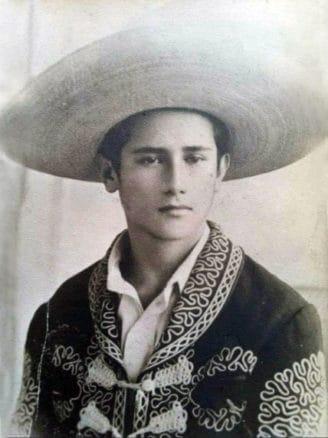

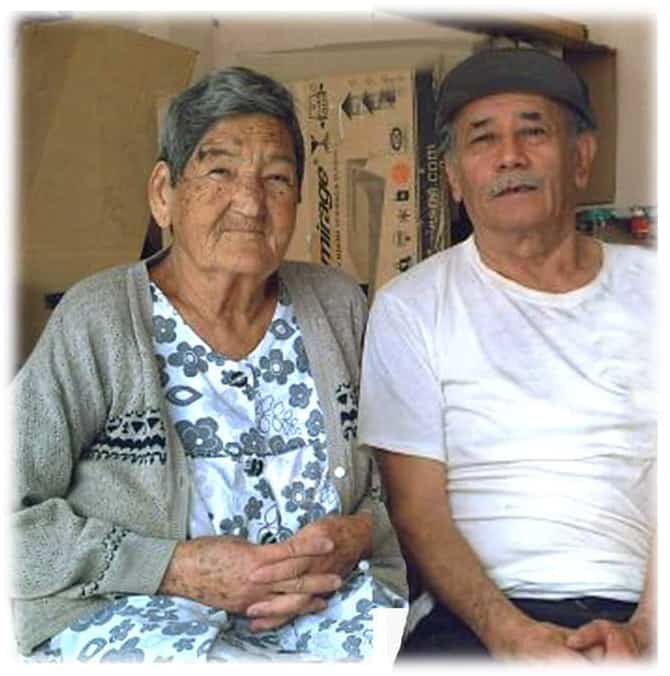

Jesús Oliva Carrillo was born on May 1, 1932 in Nochistlán de Mejía, Zacatecas, the eldest son of eight children born to Antonio Oliva Rodríguez and Donaciana Carrillo Gómez. Don Antonio played double bass and guitar in a local orchestra. Early on he taught his son Jesús the guitar, and at age 12 the boy began to study violin and solfege with maestro Andrés Antón. Of eight siblings, three became musicians: Jesús, Alfredo and Leocadio.

In 1948, at age 16, Jesús married Alicia Jáuregui Íñiguez, a native of the neighboring town of Mexticacán, Jalisco, with whom he had six children. By that time, he had switched from violin to trumpet.

His brother Leocadio remembers:

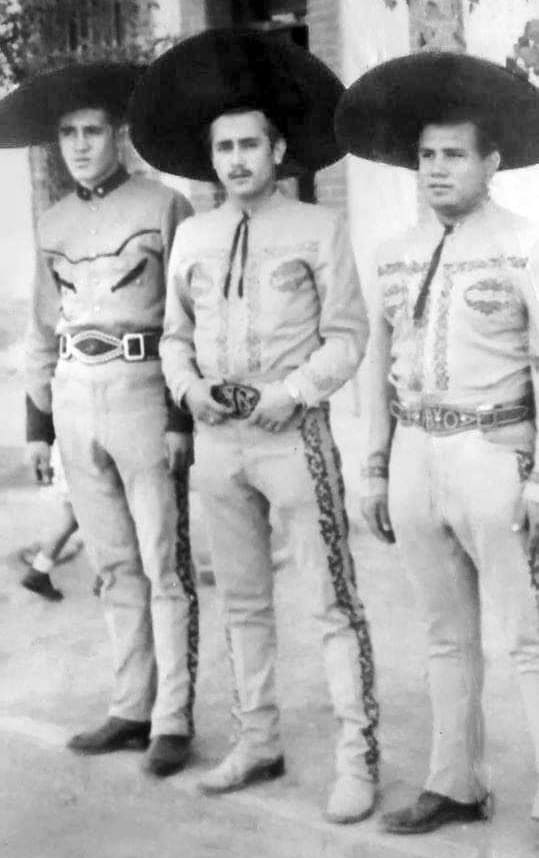

Jesús got his musical training in Nochistlán, where he started out playing with a mariachi known as Los Telos. Once he had decided on the trumpet, he went to Guadalajara where he worked with a mariachi known as Los Machetes. From there he went to Torreón, Coahuila, where he played for a year with the best mariachi in the region, Los Alteños de Juan Bocanegra.

From left to right: Jesús Oliva, unidentified, unidentified, Pedro Infante, Baldómero Aguayo, Juan Bocanegra, José Viorato, Miguel “El Cartucho” (alias “El Burro”).

Marío Santiago, a member of Mariachi Vargas de Tecalitlán for almost half a century, plays a significant role in the life of Jesús Oliva. Mario’s career has many parallels with that of Jesus, as Mario himself explains:

At first I played the trumpet, back at a time when there weren’t many mariachi trumpeters on the scene yet. Beginning in 1947, I worked for almost three years in Torreón with Mariachi Los Alteños de Juan Bocanegra. When I left that group at the end of ’49, Jesús Oliva took my place. From there, I spent a year in Ciudad Juárez with Mariachi Los Relámpagos. When I left that group, Jesús also took my place. After that, I worked for a year with Mariachi Ryesa in the city of Chihuahua until, in 1952, on the recommendation of Miguel Aceves Mejía, I went to Mexico City and joined Mariachi Vargas. Oddly enough, Oliva once again took my place when I left the Chihuahua group. It seemed like he was following in my footsteps, although I didn’t even know him yet.

Well, after two years with Mariachi Vargas, I gave up the trumpet, and in 1957 I returned to the group, this time playing violin. By the late 1950s, I had the need for an automobile, but I couldn’t afford one. Then one day someone suggested to me: “Go to the border—there you can buy an American car at a cheap price and you can legalize it here in Mexico City.” Since I’d already lived in Ciudad Juárez and was familiar with the scene there, I jumped on a bus and headed for Juarez!

Well, I spent a few days there looking for an unregistered car among friends and colleagues, and I finally bought a 1947 Plymouth sedan. I left in the afternoon for the city of Chihuahua. Since it’s over 200 miles away, I drove most of the night. When I arrived in Chihuahua at the break of day, at the first traffic light the engine began to sputter on me.

With the car lurching jerkily, I barely managed to reach a hotel, where I rented a room and slept for a while. When I woke up, I went to the restaurant where I had worked with Mariachi Ryesa years earlier. Their shift started at noon. All of my ex-compañeros greeted me, and I explained to them my problem. They recommended me a mechanic and I went to see him. When he checked out the car, he said to me: “Your engine has thrown a rod.” “How could that be?” I exclaimed. “I can fix it, but it’ll take me a week, maybe longer,” he said. I had no choice but to wait.

During that week I’d go every day to the planta where my ex-compañeros played, to eat and to visit with them. It was a restaurant-bar run by the Cruz Blanca brewery. Three new members of the band were brothers whom I’d never met. One of them was the trumpet player who’d taken my place: Jesús Oliva.

Mario continues:

This guy Jesús was extremely chummy and he had a special interest in me. He wanted to know all about my background—the egg and who laid it! He told me that I was his guiding star and that, by the hands of fate, he’d been taking my place wherever I’d been previously. The way he explained it, he believed it was his destiny to fill my shoes whenever I left a spot vacant. Now I was a violinist, and he wanted to take the trumpet spot I’d once held in Mariachi Vargas.

When they finally fixed the car, guess what? This guy stuck to me like glue! “I’m going with you, I’m going with you!” he insisted. And he left that mariachi and came to Mexico City with me. I swear I didn’t invite him — he invited himself — but I didn’t have the heart to say no, either, since he had treated me so well and had won my friendship. In fact, we later became compadres when my daughter Rocío was born.

When we got to Mexico City, I asked Jesús, “Now what are you going to do?” “I’ll go wherever you accommodate me,” he replied, “but I want to be in a good group.” So I got him a job with Mariachi Los Mensajeros, Garibaldi’s best group at the time. There was a shortage of good trumpet players in Plaza Garibaldi, and Chuy played well. They accepted him into the group, but he wasn’t satisfied there.

Next he said, “Introduce me to Mariachi México de Pepe Villa. I know all their music.” So I took him to where Mariachi México was playing and introduced him to Pepe Villa. “I know all of your polkas,” he told Pepe. Let’s see if it they give him work, I thought. But Pepe only replied, “Well, I’ll call you when there’s an opportunity,” half ignoring him. Then I recommended him to Arcadio Elías and Arcadio received him in his Mariachi Nacional, but he still wasn’t satisfied.

Federico Torres, who played in duet with Jesús when they were both members of Mariachi Nacional de Arcadio Elías, recalls: “He was a good trumpeter and a good compañero. He liked to joke around a lot.” Pepe Chávez, the guitarist for Mariachi Nacional who later directed the renowned Mariachi Oro y Plata, also remembers him: “I worked with Jesús Oliva for about a year in Mariachi Nacional. He played well. He had a very pleasant personality and was always in good spirits. ”

Mario picks up the story:

Jesús was a now member of Mariachi National de Arcadio Elías, but he kept saying to me: “I want to ascend, I want to climb higher!” “Wait a little bit,” I told him. “You’re already in a good group. Let the mariachi world get to know you little by little, and for sure you’ll receive more invitations.” But he was really impatient. He was determined to join Mariachi Vargas, but there was no opening in the group. Back then, Mariachi Vargas only used a single trumpet player, and the one holding that position at the time was the great Cipriano Silva.

Well, Silvestre Vargas had long been urged by clients and recording studios to add another trumpet to his band, until finally one day he asked me to recommend him a second trumpet player, and I recommended Jesús Oliva. That’s how he entered Mariachi Vargas. He was finally where he’d always wanted to be, but he never imagined what Cipriano’s personality would be like! (laughs) After his first run-in with Cipriano, I said, “Well, you wanted to be where I was, right? Now you see what you’ve gotten yourself into!”

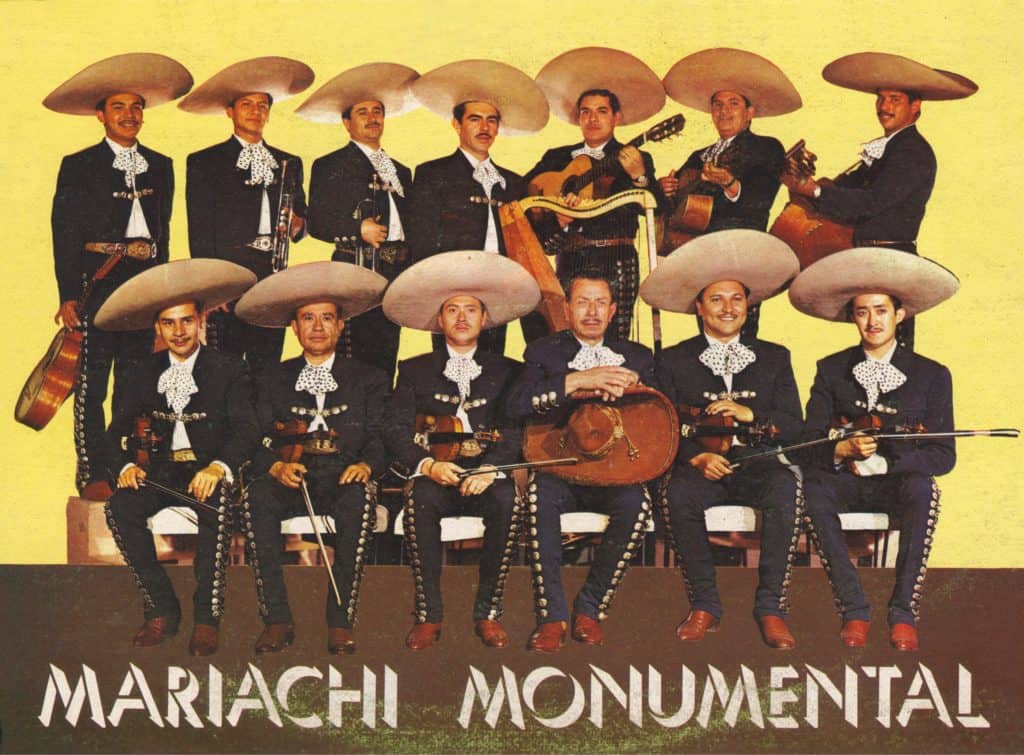

Cipriano Silva, Rafael Arteaga, Nati Santiago, Jesús Oliva, unidentified, Rigoberto Alfaro, Silvestre Vargas, unidentified child, Samuel Morales, Gustavo A. Santiago, Heriberto Molina, Mario Santiago, Luis Navarrete, Santiago Torres, Arturo Mendoza.

Back row: Cipriano Silva, Rigoberto Alfaro, Gustavo A Santiago, Arturo Mendoza, Nati Santiago, Santiago Torres, Rafael Arteaga.

Center row: Jesús Oliva, Mario Santiago, Rock Hudson, Silvestre Vargas, Jesús Rodríguez de Híjar.

Front row: Heriberto Molina, Luis Navarrete.

The following are four testimonies regarding Jesús Oliva’s nature, the duration he was in Mariachi Vargas, and the reason for his departure.

Mario Santiago comments:

Jesús was a joker and a comedian, so much so that Gustavo A. Santiago nicknamed him “El Tripalquidio” (the name of a famous clown). He always tried to be funny and would get overly-friendly with customers. Silvestre Vargas didn’t like that at all; he wanted his group members to be serious.

Rigoberto Alfaro recalls:

Yes, Jesus and I worked together with Mariachi Vargas, but only for a short period. I don’t think he was there for even 20 days when they gave him the boot. He did a lot of comic antics, but the reason he didn’t work out was because he couldn’t form a team with Cipriano, who was the group’s main trumpet player at the time.

Leocadio, brother of Jesus, explains it this way:

I think his sojourn with Vargas was short because he had difficulties with Cipriano. My brother told me he was upset because Cipriano was really stubborn and always looking for an argument, God forgive him, and for that reason Chuy planned to leave. I never knew if he left on his own or if he waited for them to fire him. I never asked.

Heriberto Molina offers another explanation for the departure of Jesús:

I came back from vacation to find two new compañeros in the group: Rafael Arteaga “El Charro” on guitarra de golpe and Jesús Oliva on second trumpet. We had been 11 members; now we were 13. I protested to Silvestre Vargas, questioning him why he had brought these new people into the group. I let him know in no uncertain terms that I had a family to support and that I wasn’t happy that I was now going to be earning less money due to maintaining unnecessary members in the group.

Although Jesús Oliva’s tenure with Mariachi Vargas was short-lived, he managed to appear with the group in at least four photographs, images that prove beyond a doubt his presence in the group. One of them is the cover of an album on the Orfeón label where he recorded in duet with Cipriano Silva. After Jesús left Vargas, Cipriano remained for several years as the group’s sole trumpet player.

Back row: Luis Navarrete, Cipriano Silva, Jesús Oliva, Arturo Mendoza, Rigoberto Alfaro, Rafael Arteaga, Nati Santiago.

Front row: Heriberto Molina, Santiago Torres, Jesús Rodríguez de Híjar, Silvestre Vargas, Mario Santiago, Gustavo A. Santiago.

Leocadio Oliva continues tracing his brother’s history:

At that time, I was with Mariachi Los Charros de Ameca de Román Palomar, and when Jesús left Vargas, Román invited him to the group. Chuy accepted his invitation and we played together in Román’s mariachi for about a year.

Los Charros de Ameca were in the studio two or three times a week, and Chuy and I recorded lots songs with that group. On records we accompanied Lola Beltrán, the Hermanas Huerta, Hermanos Záizar, Hermanos Michel, the duet Águila y Sol, Magda Franco…

Leocadio continues:

There was a lot of work in Mexico City, but the fast pace was so overwhelming that Jesus and I ended up abandoning it. We come from a small town, and the contrast between the provincia and the nation’s capital city was just too much of a culture shock for us. We both owned properties in the city of Chihuahua, and that’s where we moved back to.

Returning to Chihuahua in the mid-1960s, we formed a new group called Mariachi Zapopan where my brother Jesús and I continued to play together. Our other musician brother, Alfredo, was still with Mariachi Ryesa. We put together a respectable group and remained with it for about three years, until Chuy and I bought a paletería (popsicle shop) and we got out of the music business. Later I ended up selling him my share, then I bought another paletería in Culiacán and moved here. The business we’d started together didn’t flourish under Jesús’s management, so one day he just said, “I’ve had enough,” and sold it, moving to here Culiacán where we have a lot of relatives.

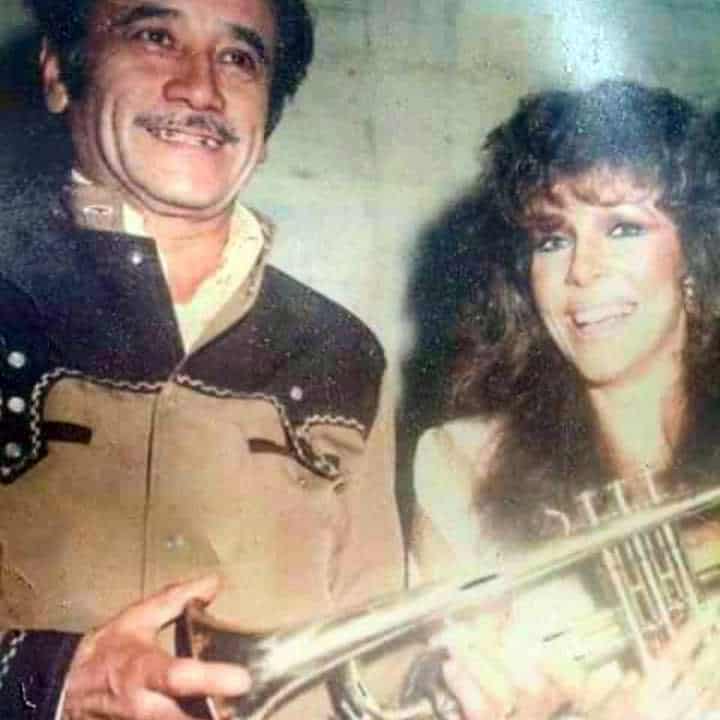

In Culiacán, Jesús went back playing to music. “I’m returning to my roots,” he would say. For about six years he was with Mariachi Perla, a competent local group. There the jefe, Guadalupe Soto, baptized him with the nickname “El Bolis,” after a brand of popsicle. In Culiacán Chuy also worked with Mariachi Imperial.

Jesús Israel Oliva, son of don Chuy, continues the story:

In 1999, my dad was bedridden for six months due to complications related to diabetes. They amputated two of his toes. Once he recovered, he couldn’t stand for long periods anymore, and he never worked as a mariachi again. For a long time he’d had a musical friendship with a priest named Father Ojeda who liked to compose hymns on the organ. My dad helped this priest adapt his compositions to mariachi arrangements. That was the only musical activity my father had during his later years. He became a widower when my mother passed away in 2009.

On April 30, 2020, Children’s Day (Día de los Niños), at 11:00 p.m., Jesús Oliva Carrillo suffered a sudden heart attack at his home in the Colonia Gabriel Leyva neighborhood of Culiacán, just one hour before he would have turned 88 years old.

Francisco Javier Soto Villa “El Negro,” treasurer of the local mariachis union in Culiacán, brought music to the wake:

When my brothers and I started out in Mariachi Juvenil Culiacán about 30 years ago, don Chuy was the one who taught us. He was our first maestro. When he passed away, basically the same group of brothers and relatives, now called Mariachi Internacional Culiacán, played at his wake in expression of our gratitude. First we had to get permission from the authorities, due to the pandemic.

The earthly remains of the perpetually smiling Jesús Oliva “El Bolis”—excellent musician, good friend and exemplary family man—now rest forever in the Panteón Civil of his beloved adoptive town of Culiacán. He is survived by seven brothers and sisters, his four children Jesús Israel, Rodolfo Alfredo, María del Rocío and Sandra Alicia; eleven grandchildren, three great-grandchildren, and three great-great-grandchildren.

What was Jesús Oliva’s main contribution to mariachi music? While some point out that he was never a full-fledged member of Mariachi Vargas de Tecalitlán and was only provisionally “de prueba,” it is important to state that he was part of Mariachi Vargas’s earliest experiment to make the trumpet duet a permanent feature of the group, an evolutionary process that wouldn’t be consummated until the latter part of the 1960s or the early part of the 1970s.

Federico Torres, trumpeter with Mariachi Vargas for over five decades, concludes:

It depends on how you analyze it. Remember that in its entire history, Mariachi Vargas only had two great, stellar trumpet players: Miguel Martínez and Cipriano Silva. All the rest of us were “de prueba.”

What a great legacy!